Climate investments in the EU economy grew by 9% in 2022. A report published by Institute for Climate Economics (I4CE) finds that the European Green Deal is gaining economic momentum but investments in modernising energy, transport, and buildings must still double for the EU to hit 2030 climate targets.

Climate investments made today shape Europe’s future

To mitigate climate change and ensure Europeans can access clean, affordable, and secure energy, the EU set itself several ambitious targets for 2030.

Reaching them requires significant investments in the EU economy. Investments made today shape Europe’s future. Renovating a home reduces energy demand for the next decades, making the economy more resilient to fossil fuel crises. Building a new wind power plant increases the amount of cheap renewable electricity the European industry can access to build its competitive sustainability.

In addition to their positive climate impacts, climate investments promote many EU policy priorities. Wind and solar power deployment decreases electricity prices and thus helps contain inflation (IEA, 2023c). The deployment of heat pumps strengthens EU energy security by reducing its dependence on Russian gas (Bruegel, 2023b). The replacement of internal combustion engine vehicles with battery-electric ones reduces air pollution and improves public health (EEA, 2023). Climate investments are also critical to create lead markets for the European industry to build its competitive edge in the global cleantech race (I4CE, 2023e). Finally, those investments are a democratic imperative as European citizens consistently want the EU to keep prioritizing climate action (Eurobarometer, 2023).

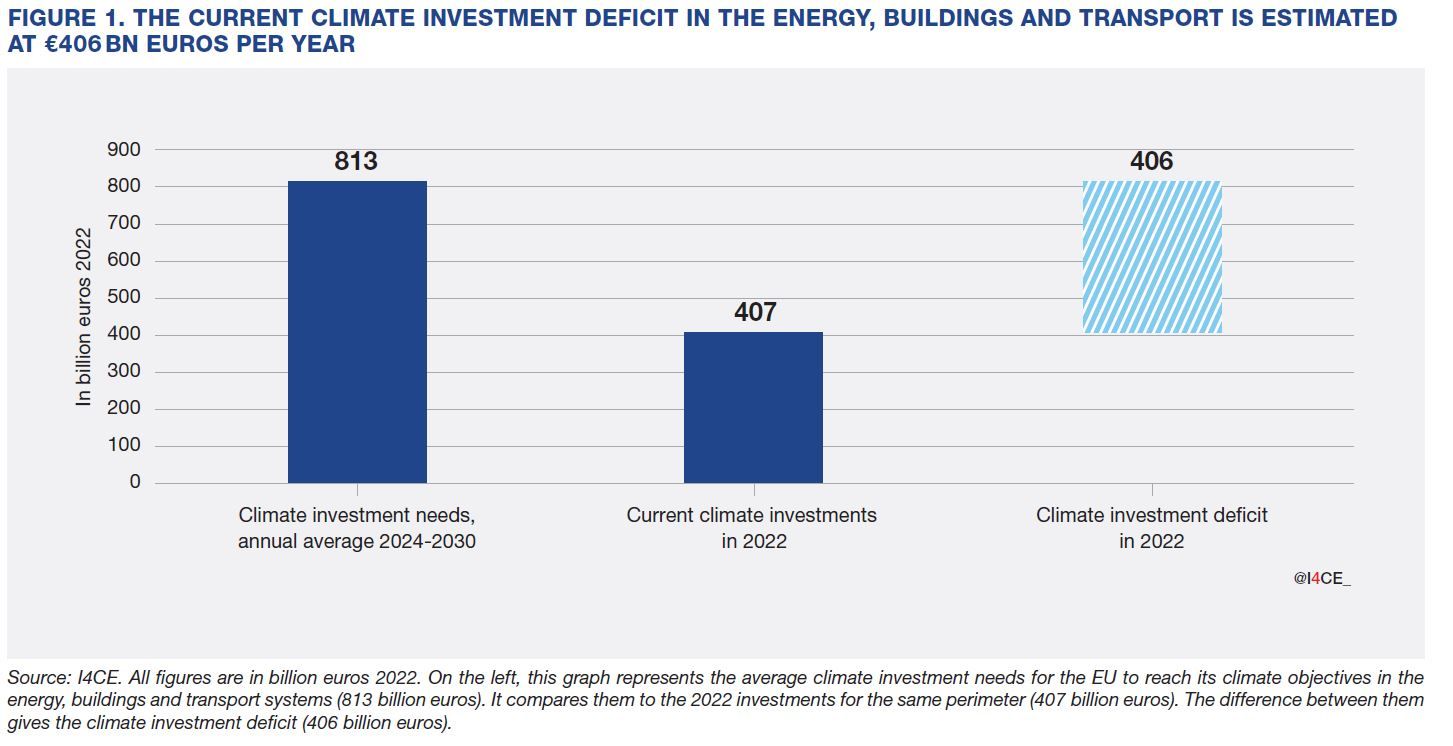

Better tracking public and private climate investments will help measure structural changes in the EU economy. This report estimates the climate investment deficit, i.e. the difference between A) the total investment needs required annually by 2030, to achieve the EU 2030 targets and B) the actual public and private climate investments happening in the EU economy in the latest available year.

This climate investment deficit is a key predictor of the structural progress achieved by the EU economy: the smaller the deficit, the more the EU economy delivers structural changes. Looking beyond headline figures, a granular analysis helps understanding the roots causes of the climate investment deficit as investments in some sectors are doing better than in others, with sectors that can even be in a situation of climate investment surplus.

However, the EU lacks a consistent tool to ensure the yearly monitoring of the climate investment deficit. This is why the European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change, a scientific group created by the EU Climate Law and attached to the European Environment Agency, recently called on the EU to ‘strive for a more granular and accurate overview of required and actual investments in climate mitigation to monitor and assess progress’ (European Scientific Advisory Board on Climate Change, 2024).

This report helps fill this knowledge gap.

Climate investments in the EU27 economy grew by 9% in 2022, reaching 407 billion euros in 22 sectors

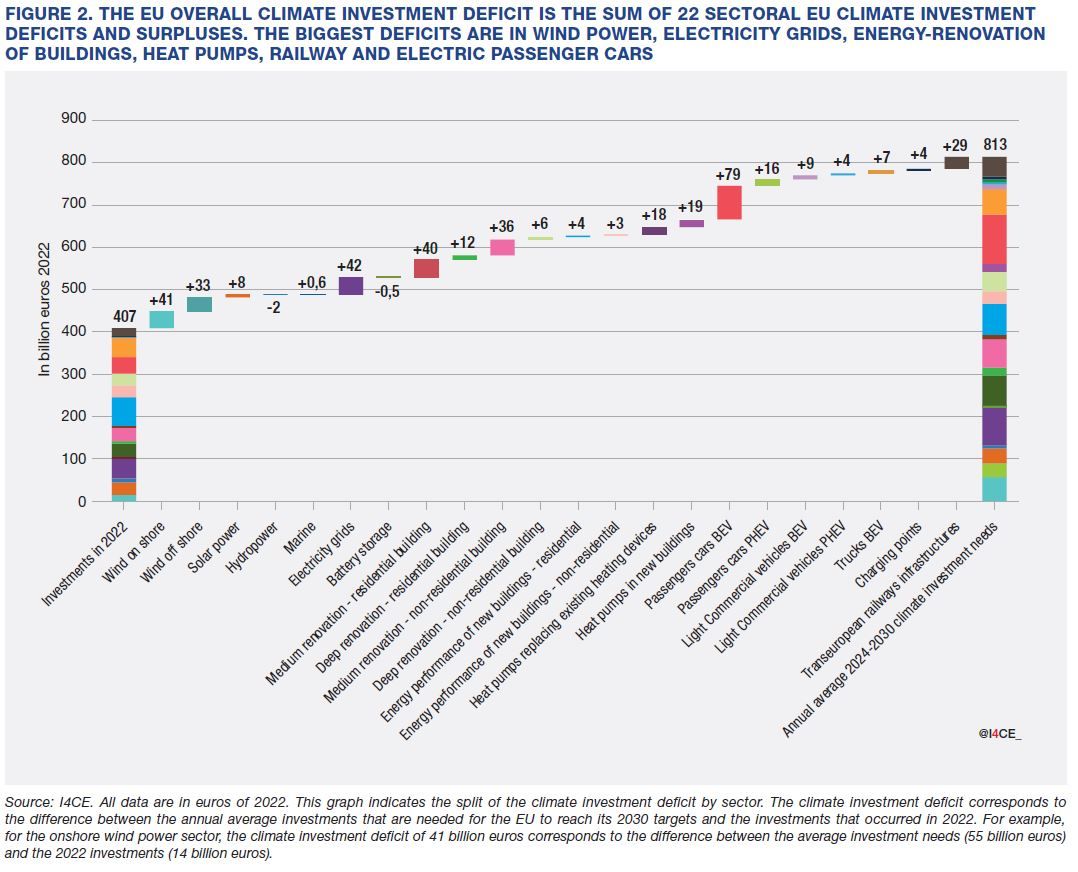

This report tracks the EU27 public and private investments made in 22 sectors (including wind power, building renovation, electric cars, and others presented in Figure 2) that are critical to the transformation of the energy, building and transport systems. Investments in those sectors have been growing by 9% between 2021 and 2022, reaching 407 billion euros in 2022 – or 2.6% GDP.

At a granular level, our research found that recent trends in EU27 investments in our covered sectors vary. Investments in solar panels and electric cars increased significantly. Heat pump investments even doubled between 2020 and 2022. This suggests that the EU economy is going in the right direction in those sectors, albeit too slowly given the EU level of ambition. Our research however found wind power investments collapsing in 2022, down to their lowest levels since at least 2009.

The European economy needs to double its level of climate investments to deliver the EU 2030 targets

Our research compared 2022 levels of investments with the levels of investments needed each year forward to deliver the EU 2030 targets in each one of the 22 sectors covered in this report, covering roughly buildings, transport and energy systems. This leads to an overall average yearly investment need of at least 813 billion euros, or 5.1%, of EU GDP. As real-economy investments reached 407 billion euros in 2022, this leaves a European climate investment deficit of 406 billion euros per year, or 2.6% GDP. By comparison, explicit and implicit fossil fuel subsidies in the EU have increased and reached 290 billion euros in the year 2022 (IMF, 2023).

In other words, current levels of public and private investments represent already half of total investments needed to occur every year to deliver on the EU 2030 targets for the energy, buildings, and transport sectors. Yet doubling those investments is essential to deliver the economic, geopolitical and climate benefits EU policy makers committed to.

Hydropower and battery storage lead the way, wind power is struggling

Looking at all the 22 sectors covered by this report, our research points out that in only two sectors, hydropower and battery storage, 2022 climate investments were higher than the annual investment needs for those two sectors. They are therefore in a situation of climate investment surplus.

All 20 other sectors suffer from a climate investment deficit, of varying proportions. For instance, 2022 investments in wind power represent only 17% of total annual investment needs. Conversely investments in solar panels represent already 78% of total annual investment needs.

In absolute terms, the climate investment deficit in some critical sectors would be relatively easy to bridge. For instance, closing the climate investment deficit in charging points for electric vehicles would require additional public and private investments of only 4 billion euros per year (cf. Figure 2).

Figure 2 “The EU overall climate investment deficit is the sum of 22 sectoral EU climate investment deficit and surpluses”

Assess better: EU institutions should develop their own transparent and comprehensive yearly monitoring of the EU climate investment deficit

Given its significance, the European Commission needs to better assess and address the EU Climate Investment Deficit, or risks seeing the Green Deal failing to deliver on its economic, social and environmental promises. To better assess the climate investment deficit, EU institutions should build on this report’s research and deliver their own, needs-driven and more accurate, granular and comprehensive assessment:

- More accurate: access to data has been a challenge, especially when it comes to the building sector. Whenever faced with different methodological options, we consistently opted for the most conservative one. This may lead to some under-estimation in some sectors, and over-estimation in others.

- More granular: our report relies on EU27 data. A more granular approach could look at national and regional data that are relevant for national and local public policies. National governments and research organisations may use the methodology I4CE developed for France and the EU, and adapt it to be applied to a specific national economy.

- More comprehensive: our report only covers 22 sectors in the energy, building, and transport systems. Due to a lack of access to reliable data, critical sectors such as industry, agriculture, and climate change adaptation are not covered by this report.

The Institute for Climate Economics (I4CE) is pursuing and expanding its analysis to provide an up-to-date annual estimate that can be used by the EU Commission, Council and Parliament, as a new mandate is set to begin after the 9 June 2024 elections.

Address better: closing the European Climate Investment Deficit with an EU long-term climate investment plan

Addressing the climate investment deficit requires a comprehensive approach that involves existing and future regulations, carbon pricing systems, and public finance schemes. Given the scale of the current deficit, and the expected reduction in EU climate funding in the years to come (Bruegel, 2023a), some additional EU public funding is likely required to contribute to closing the Climate Investment Deficit.

A granular assessment of the climate investment deficit informs the debate over the right articulation of public funding and private financing. By their very nature, some sectors depend on public funding, such as the renovation of primary schools. Some even depend on a degree of EUlevel funding, such as the trans-European interconnection of electricity and railway infrastructure. Others, may largely rely on private finance if the right framework conditions are set.

The quantity, nature and sectoral targeting of EU funding will therefore depend on the economic sectors concerned and political choices.

This report concludes with a list of several political questions that are beyond the scope of our research. A debate on a future EU long-term climate investment plan should answer them. This includes the public funding tools to crowd-in private funding, the role of Member State public funding that can be supported by EU funds and policies and/or constrained by EU fiscal rules, as well as the debate on potential sources of new EU funding, and their articulation with overall EU policy priorities.

To nurture this debate, this report provides granular and transparent evidence to support informed decisions by EU citizens and policymakers, before and after the 9 June 2024 EU elections.