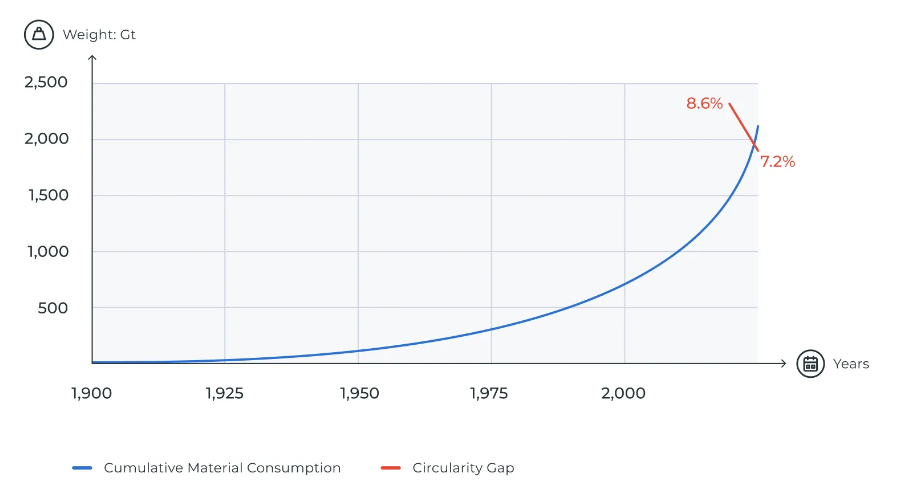

Over the past five years, the number of discussions, debates and articles related to the circular economy has almost tripled in spite of the global circularity rate falling from 9.1% to 7.2%. This is according to the Circularity Gap Report 2024, launched by Circle Economy Foundation and Deloitte today. The report moves from theory to action by identifying how the three main enablers of policy, finance and labour can drive sustainable progress worldwide.

In the last five years, humanity consumed a whopping 500 billion tonnes of materials—nearly equal to what was consumed during the entire 20th century. The global circularity rate has fallen steadily from 9.1% in 2018, when Circle Economy Foundation began measuring, to 7.2% in 2023. This means that out of all the materials consumed worldwide, we’re consuming more virgin materials than ever—while the share of secondary materials is in decline.

Accelerating progress toward a circular economy means addressing the root causes of linear impacts and changing the rules of the game to favour circular practices. The Circularity Gap Report 2024 outlines how policy, finance and employment reforms can reshape global systems to promote circularity.

‘Leveraging the Circularity Gap Report, stakeholders are able to prioritise their circular roadmap based on a data-driven analysis. Policymakers, industry leaders, and financial institutions can agree on focus areas and work collaboratively on the systemic change needed to stay within our planetary boundaries,’ says Ivonne Bojoh, CEO of Circle Economy Foundation. ‘To ensure the transition to a circular economy is just and fair, circular solutions must be designed with the world’s most vulnerable populations in mind, then these solutions will reduce inequalities across workforces and increase job opportunities worldwide.’

Ultimately, the report proposes a strategy to break free from flawed economic practices known to be socially and environmentally exploitative. This will require unlocking capital, rolling out bold, contextually appropriate policies and closing the sustainable and circular skills gap.

Policies and legal frameworks can incentivise sustainable and circular practices while penalising harmful, linear ones. Wealthy countries could achieve the most impact by adjusting regulations in the construction and manufacturing industries. Examples include incentivising retrofitting and reusing buildings (and their components and materials), developing certification and warranties for secondary building materials, setting standards for product durability, and strengthening the Right to Repair legislation.

In middle-income countries, fostering circular agriculture and manufacturing will be a top priority. Local governments could, for example, impose and enforce public bans and limits on pollution, mandate Extended Producer Responsibility schemes and require a minimum amount of recovered materials for all new production while directing funds to regenerative farming.

Lower-income countries could prioritise sustainable development through circular policies in construction and agriculture. These include relieving debt and improving access to development and transition capital, securing smallholder farmer rights and incentivising the use of local, organic and secondary materials in construction.

To unlock finance for circular construction and manufacturing in high-income countries, the study suggests rethinking accounting standards and practices as well as rolling out taxes to increase the price of unsustainable products.

In emerging economies, governments can shift subsidies away from polluting practices in agriculture and manufacturing and towards clean, regenerative ones. In addition, they can ensure all future investments align with ecological and social wellbeing standards.

Development and transition funds could be used in lower-income countries to support circular measures across key sectors like agriculture and construction—regenerative farming and smart urban planning, for example.

Finally, the report underscores the need to enable a just transition by bridging labour and skills gaps. This means education curricula—especially for vocational education—should include green disciplines and skills. Short-term courses could be a solution to meet the immediate and growing demand for green jobs, from renewable energy technicians to repair specialists.

In addition, developing countries could formalise informal employment and focus on making emerging jobs decent, inclusive and well-paid to ensure a just transition for all.